Single-cell profiling adult human neural stem cells

Neural stem cells (NSCs) of the subventricular zone (SVZ) remain mostly in a dormant state in the adult human brain after closure of the neurogenic period at birth. These dormant progenitors rarely proliferate or produce neurons. How an adult human NSC is maintained in this quiescent state and could be triggered to re-activate is still unclear.

In this recent publication at Nature Communications, Vanessa Donega, Elly Hol and colleagues unravel a possible mechanism through which progenitors of the adult human SVZ are maintained in a dormant state. They used state-of-the-art single-cell RNA sequencing to profile the molecular characteristics of a major neural stem cell niche in the adult human brain. They identify the Wnt pathway antagonist SFRP1 as a possible signal that promotes neural stem cell quiescence in the aged human SVZ. Furthermore, they show that inhibition of SFRP1 stimulates neural stem cell activation both in vivo and in vitro. This work opens up future possibilities to stimulate neural stem cells of the human brain to promote repair.

“I am very happy that this work is out, and I am excited to continue investigating the role of SFRP1 in regulating neural stem cell quiescence.” Vanessa Donega

This work was performed primarily at our Translational Neuroscience department of the UMC Brain center. This work was supported by ZonMw, by the MAXOMOD consortium, a Ministry of Science and Technology of China grant, Theme-based Research Scheme, Health and Medical Research Fund and CUHK Direct Grant

Astrocyte function in early-stage Alzheimer’s disease on GLIA

Astrocytes are literally the star cells of our brains! PhD candidate Christiaan Huffels, from the group of Elly Hol, recently published a study on astrocyte function in early-stage Alzheimer’s disease in the scientific journal GLIA.

Astrocytes are literally the star cells of our brains! PhD candidate Christiaan Huffels, from the group of Elly Hol, recently published a study on astrocyte function in early-stage Alzheimer’s disease in the scientific journal GLIA.

Alzheimer’s Disease is the main form of dementia in the elderly, characterised by the accumulation of amyloid-ß protein. In this study, Huffels and his colleagues examined the role of astrocyte function in Alzheimer’s Disease. They focused on Kir4.1 expression and function, which is an ion channel that is essential for the role of astrocytes in the maintenance of tissue ion homeostasis. Despite localised increase in Kir4.1 protein expression, astrocyte Kir4.1 channel dysfunction is likely not involved in the pathogenesis of early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. This study hereby provides more in-depth insight into the development of early-stage Alzheimer’s disease and provides directions for future research. After this study was accepted for publication, one of the images was selected for the cover of GLIA.

Christiaan was happily surprised: “I thought it was great that they asked me to provide an image for the cover and immediately agreed, as this can draw extra attention to the interesting study we performed.”

The research was primarily performed at our Translational Neuroscience Department at UMC Bran Center, in collaboration with the University of Amsterdam and University of Bonn. The study was supported by the University of Amsterdam, ZonMW, and Alzheimer Nederland.

Research paper on Pharmacology teaching

Teaching Pharmacology to (bio)medical students is a prominent role of the department of Translational Neuroscience. Through the years the method of teaching basic science subjects like Pharmacology has changed. As a result, we no longer teach pharmacology as an independent subject with a separate final examination. Instead, it is integrated with other subjects.

This integrated medical curriculum has advantages, such as better integration of clinical and preclinical subjects. It also has its disadvantages, such as the absence of separate examination on Pharmacology. Due to curricular integration, students could still graduate despite having sub-optimal knowledge of the subject.

Our faculty members Rahul Pandit, PhD and Mirjam A. F. M. Gerrits, PhD continuously improve the teaching quality within the department and UMCU. In the current paper, they aimed to investigate and address the drawbacks of the methods of examination within the integrated medical curriculum. To achieve this, they looked into one specific aspect of Pharmacology (Pharmacokinetics) and shown that the student knowledge is on this topic is sub-optimal. In addition, they suggest a few solutions to address this issue. Please visit here to view the article published as open access in Medical Science Educator.

No need for competition

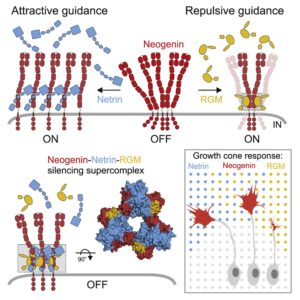

During brain development signaling proteins guide traveling neurons and their axons. These proteins do so by binding the receptor on the cell membrane of the neuron. For a long time it was thought that when two different proteins are close to the receptor they compete for binding. However, we found that instead of competing for binding, two different proteins can both bind the receptor at the same time. When this binding occurs the receptor is turned off, meaning that the neuron turns insensitive to signals. Because we now better understand this mechanism we might be able to use this knowledge in the future to answer disease-related questions.

During brain development signaling proteins guide traveling neurons and their axons. These proteins do so by binding the receptor on the cell membrane of the neuron. For a long time it was thought that when two different proteins are close to the receptor they compete for binding. However, we found that instead of competing for binding, two different proteins can both bind the receptor at the same time. When this binding occurs the receptor is turned off, meaning that the neuron turns insensitive to signals. Because we now better understand this mechanism we might be able to use this knowledge in the future to answer disease-related questions.

Reactive astrocyte nomenclature, definitions, and future directions

Together with other astrocyte researchers, Translational Neuroscience researcher Elly Hol wrote this highly needed paper for the field. This paper will be an important overview for all interested in reactive astrocytes in brain diseases.